For a great deal many of you, swimming is on indefinite hiatus.

Practices are canceled.

Trials are postponed.

Senior year championship meets are toast.

And during these uncertain times, where we step back to be there for the greater good, there’s a simple thing I hope you hold onto.

The Process is the Big Win.

By now, you have likely had the “process is what matters” pep talk from your coach.

They told you that the work you did was the victory. That the investment of time and energy wasn’t in vain. That the things you learned about yourself during the season can never fully be explained in a medal, placing, or time.

If you’ve read more than a handful of my newsletters, blog posts, or own either of my books, you know that I bang on the process like a drum on a six-pack of Red Bull.

And I hope you listened.

And I know—without that big meet, the shave-and-taper, the opportunity to see what you could really do, the process feels incomplete.

The work you did feels unresolved.

The time, energy, hard work… The self-identity you created during the long stretches of the season feels incomplete.

And I know it’s hard to value the process when it feels incomplete without that result, and when emotions are running high.

You are feeling frustrated, and things feel super unfair.

And I want you to feel angry.

Feel the frustration.

Grieve.

It’s okay.

These feelings are normal and to be expected.

And when you are ready, I’d love for you to consider the story of an Olympic champion who had some solid stuff to say about the importance of the journey.

Of your journey.

*

It’s an Olympic year, and for a lot of swimmers across the planet, their Olympic dreams are in disarray.

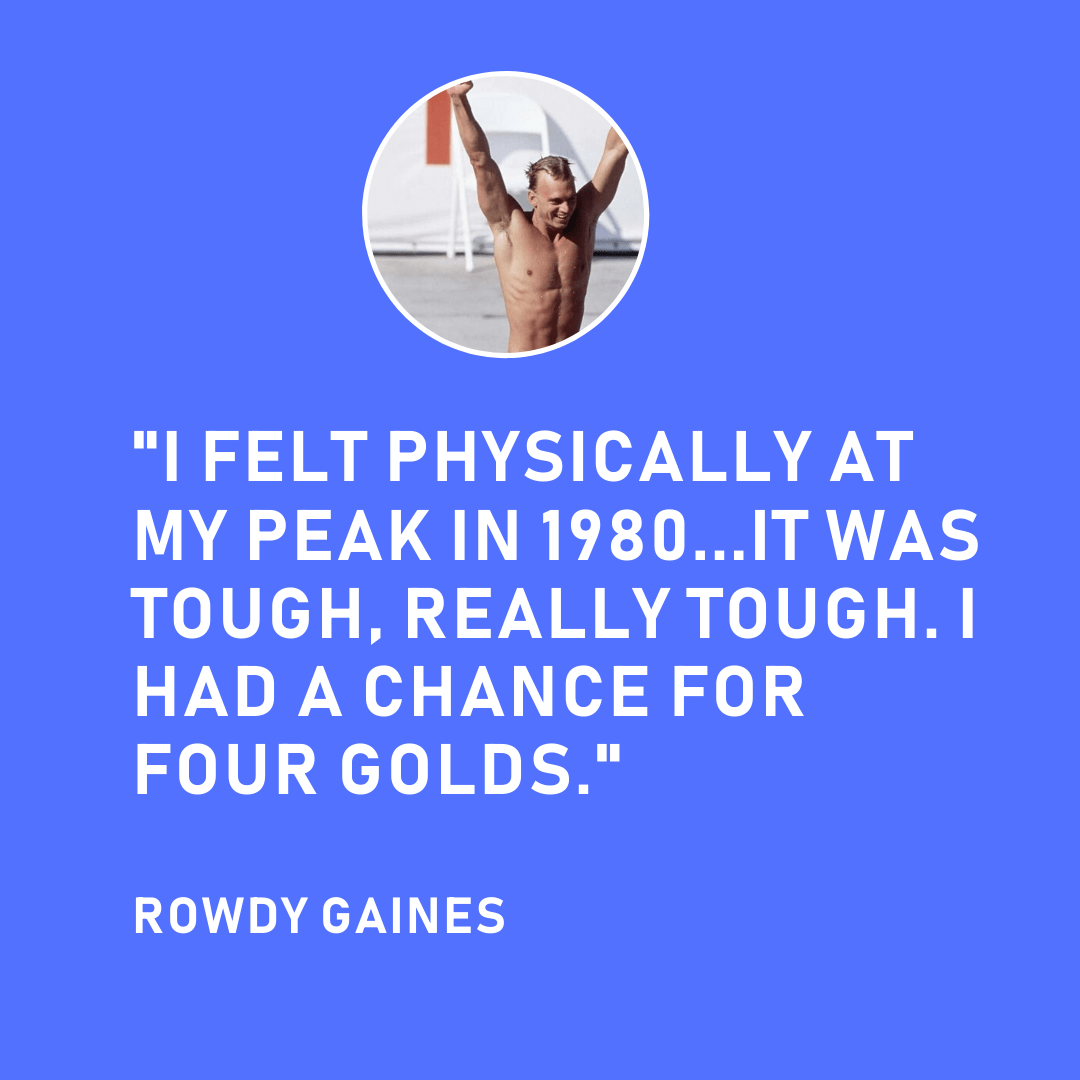

Back in 1980, the Olympic dreams of a generation of athletes were dashed when the Americans, and many Western countries, boycotted the Olympics to be held in Moscow later that year.

The boycott was devastating for 21-year old American freestyle specialist Rowdy Gaines.

He was as close to a sure bet as there was for gold in the 100 and 200m freestyles. Two relay medals lay in wait as well.

The decision to boycott wasn’t made overnight. There was months of uncertainty leading up to it.

The idea had initially gained serious traction in December of 1979. Ultimatums were laid down by the West in January. The Russians ignored them through February.

The boycott was in place by late February.

No American athletes would be going to the Games.

In the ensuing months, there were several attempts at salvaging the Games.

All the while, athletes kept training, hoping that they would get a chance to put their process to work on the biggest stage.

In April 1980, the USOC informed the International Olympic Committee that the US could still send a team of athletes to the Olympics if there were a “spectacular change in the international situation.”

There wasn’t.

In May, the IOC met with the Russian General Secretary Brezhnev and US President Carter to try and find a way to have the Games go on.

Both sides dug in.

The Moscow-hosted Games went on, while American athletes (and athletes from 65 other countries) stayed home.

*

Four years later, it would be the Russians turn to boycott the Olympics, this time held in Los Angeles.

During that four-year span, Gaines, once the dominant freestyler on the planet, struggled with doubt and uncertainty.

After the 1983 Pan Am Games, where Gaines swam slower than his PBs and failed to win the 200m freestyle, an event he held the world record in, his confidence was at an all-time low.

Was it worth it to keep going?

Had his Olympic dream passed him by?

“For the first time, I felt old. I had doubts. I sat down with my parents, my coaches, and my friends, all of whom really helped me. And in the end, I decided to go for it — win, lose, or draw — because otherwise I would never know,” Gaines said.

A year later, at the Los Angeles Olympics, Gaines would have his Olympic moment.

Two, in fact.

He would win the 100m freestyle and two more relay golds.

Years later, Gaines reflected on the adversity and uncertainty that had come about as a result of the 1980 boycott.

In many ways, the boycott had steeled him and prepared him for tougher things ahead.

And a much more meaningful victory.

“It was a blessing in disguise.”

*

Uncertainty, setbacks, adversity—they present opportunities and doorways to something greater.

And I know that it’s hard to see the better things ahead when we are enveloped in fear and frustration.

We can’t always see what it is, or where it will take us, but making the best of a bad situation guarantees that the path is one that you can be proud of.

At the end of the day, all you can really do is focus on your process.

On being the best swimmer you can be each day, whether or not that means you have access to a pool.

*

If you need to vent, if you are worried about not being able to finish your season or career on a high note, or you just want CAPS-scream at someone, let me have it.

I would love to hear from you.

Stay safe, healthy, and take care of one another.

Olivier

You can contact me anytime via my weekly newsletter or on Twitter.