Nelson Diebel had made up his mind. The 21-year old breaststroker had clambered up a fantastic looking water slide and was going to hurl himself down it.

Down on the pool deck was his coach, Chris Martin. Yelling at him that he couldn’t do it. The Olympics were a couple weeks away.

Get down, you are going to hurt yourself.

No!

Like a child taunting a parent, Diebel remains at the top of the water slide for around 15 minutes as coach and athlete argue back and forth.

“Not so close to the Olympics,” Martin recalls later. “It wasn’t worth the chance. He got mad. He climbed to the top of the slide and wouldn’t come down. He just sat there. We yelled at each other.”

Diebel, Martin reminded him, had a history of getting himself injured.

A few years earlier he’d obliterated both of his wrists jumping off a railing at the Peddie Pool. His feet were wet and slipped on take-off, missing the pool. The tiled pool deck, however? Oh yeah, he nailed that, using his wrists to buttress a face-first impact. Five plus hours of surgery and five pins later Diebel was the owner of two casts that he would wear for the next eight weeks.

Eventually, Diebel climbs down.

“We argued some more,” Diebel says. “Then we were all right. I told Chris I was going to make all of this worth it. I told everyone I was going to win. If you do, it’s just confidence. If you don’t, I guess it’s arrogance.” [1]

An unstoppable force meeting an immovable object

As a kid Diebel had been a “geeky goody-goody.” That all changed as a 12-year old when his parents divorced. Whether it’s drugs, petty theft, or getting thrown out of school for fighting, Diebel looks for trouble and has no difficulty landing right in the middle of it.

By the time he is 16, he is sitting in the admissions office of the Peddie School in Highstown, New Jersey. It’s last chance time. His mother, Marge, is on her last nerve. To grease his acceptance Diebel has fibbed on the application, writing “swimming” as one of his interests.

“Probably one of the largest lies I have ever told in my life,” he says [2]. His age group swimming career had been casual at best. He typically skipped swim practice to go find for some good old fashioned shenanigans to get himself into.

The head coach at Peddie is brought in. Chris Martin, 6’2” and 240 pounds stares back at him. If there is one word to describe Martin and his coaching style, it’s intensity.

“The first thing I want you to know is that I am a tyrant!” says Martin.

Diebel shifts in his seat.

“The second thing is, if there’s going to be any fighting, it’s going to be with me!”

The verbal avalanche continues for ten minutes. Diebel’s mother quietly looks at the ceiling, her prayers answered.

Terrifying, is how Diebel would remember it.

Channeling the rage

Over the following six years, the built-like-a-linebacker coach and the rebel-without-a-clue swimmer battle. A constant clash of egos, with coach and swimmer sparring, yelling and frustrating one another.

“This has not always been a pleasure,” Martin admits later. “I’ve come pretty close to telling him to get lost several times. Last Christmas, when he wasn’t doing the training or something else I wanted, I said, ‘This isn’t worth it.’ Nelson told me he would make it worth it.” [3]

Despite the acrimony, things are improving for Diebel. He has a gift for breaststroke, which matches his personality and outlook.

With Diebel’s rage being funneled into the pool–“He was the angriest kid I’ve ever seen,” Martin recalls—he quickly improves. The fury, the rebelliousness, and the idleness are channeled into the water and the classroom.

Two years later he qualifies for the 1988 US Olympic Trials and finals in both breaststroke events. He sees for the first time that he can really go somewhere with the sport. Martin tells him that he can be on the team going to the 1992 Olympics.

Although his life is straightening out, the rebel look sticks. The leather jacket, brass knuckles, and silver rings littering his fingers.

Oh, and the earrings.

By 1992, Diebel has a line of earrings down his left ear. Over the years Martin has used them as bargaining chips.

Diebel can get the first earring if he makes the honor roll. The second earring? Win the 200m breaststroke at nationals. The third? Well, win the 100m and 200m breaststroke at nationals, which Diebel does in 1990.

With the Olympics on the horizon in 1992, Diebel is battling chronic shoulder pain. He has to cut down on training heading into US Trials. His stronger race—the 200—suffers as a result of the diminished training. But he is sharper for the 100, breaking the American record in a time 1:01.40 and booking himself a ticket to Barcelona.

Diebel heads for the Olympics as “a contender, but not one of the favorites,” according to Bob Costas of NBC Sports.

But don’t tell Diebel that.

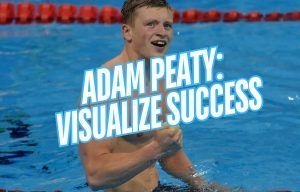

“I would be unhappy if I don’t get the gold,” he says simply.

Rebel with a medal

The 100m breaststroke is on the first day of swimming events at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Diebel qualifies third fastest coming out of prelims, putting him in lane three.

Assigned to one of the gutter lanes is Hungarian Norbert Rózsa, having snuck into the final with the eighth fastest time in the morning. Rózsa has broken the world record three times in the event over the past year and despite the less-than-awesome lane is the favorite to win.

The finalists are paraded out, and it’s vintage Diebel. He has a USA flag bandana on his head. Earrings glittering in the sun. When each swimmer has his name and country announced, Diebel is off laying in the shade.

As the race gets underway Diebel is aware of the swimmers around him. To bottle his energy and swim his race. He knows to expect to be at the hip of one of the swimmers in the next lane at the first 50. The guy likes to go out like a rocket–don’t let it mess with you.

Diebel turns third at the halfway mark. Out in lane eight Rózsa is leading the charge, but by 75m it is anyone’s race, eight heads bobbing and lunging in a straight line across the pool.

With ten meters remaining Diebel surges, charging for the wall, his shaved head and mirrored goggles bouncing the Spanish sun.

He reaches for the touchpad on a full stroke and spins to see the scoreboard. There are a couple moments as Diebel works out that he’s actually won.

Gold. Olympic record. A clenched fist shoots for the sky. Soon followed by another.

“I went in with the attitude that I could win, and that I would win.”

The Power of High Expectations

High expectations are a tricky thing.

We usually have them for ourselves in terms of what we think we are capable of, but rarely do we match this with action. Although we are reasonably sure we could do big things, we resist. We lean towards self-doubt.

When someone else tells us what we are capable of being better—and how we are falling short—we get our back up. We get defensive. Our ego tells us that we are doing well enough, that we are perfect, and that we are being unfairly attacked.

But when someone expects better of us it’s because they know that we are capable of more. They believe in us. There is no greater compliment.

The high expectations our coaches, parents and teammates have of us should push us to believe in ourselves too.

“Chris is 100 percent of the reason I am here,” Diebel says. “I was so down on myself when I got to Peddie. He was harsh on me, but it was obvious he believed in me and my swimming. That finally made me believe in myself.”

Martin’s expectations of Diebel helped the rambunctious 16-year old shift his focus and energy. High expectations require high effort, and this helped steer Diebel away from the stuff that had been getting him into trouble.

While we don’t all want or need a “tyrant” in our lives to push us towards excellence, it’s worth taking stock of the people you do decide to surround yourself with.

Do they have high expectations of you? Do they think you are capable of bigger and better things? Are they helping or pushing you to bring out the best in yourself?

It can be tempting to shy away from people who have high expectations of you because you worry about disappointing them. Or we avoid them because they shine a light on the way we are actually behaving (not as great as we perhaps would like) and the ways in which we are short-changing ourselves, which bruises our ego.

Don’t fear the high expectations. They are there for a reason. Because you are worthy of them.

“You’re going to make this hard all the way to the end,” Martin said once Diebel climbed down from the water slide.

Diebel smiles that trouble-maker smile.

“It will be worth it.”

More Stuff Like This:

Olympic Champion Tom Dolan: Adversity is Confidence in Disguise. Some swimmers buckle under adversity and setbacks–others use it to steel themselves for the best performances in the history of the sport.

Katie Ledecky : Train the Way You Want to Win. In the 200m freestyle at the Rio Olympics the gold medal came down to the finish. Here’s how Ledecky won gold a million times over in practice.

Image: Neal Simpson | AP Images