Fed up with being sidelined by swimmer’s shoulder? Here’s your ultimate guide to fixing and preventing shoulder injuries from swimming.

In this guide to swimmer’s shoulder, we are going to look closely at the most common injury swimmers experience in the water.

More specifically, we are going to look at:

- Just how often swimmer’s shoulder happens

- The more common causes of swimmer’s shoulders

- Tips on how you can train around injured shoulders

- And some actionable tips for helping fix and prevent swimmer’s shoulder.

Let’s dive right in.

How Common is Swimmer’s Shoulder?

If you’ve invested even a moderate amount of time training up and down and around the black line you have become intimately familiar with the term ‘swimmer’s shoulder.’

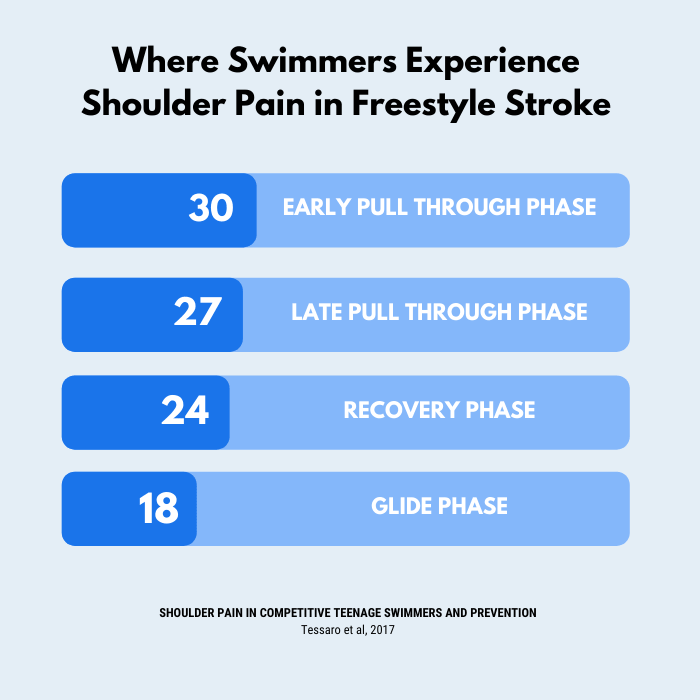

Given that swimmers annually perform hundreds of thousands of arm rotations it should be of little shock to learn that this type of work and frequency places a lot stress on the shoulder musculature and joint.

As a result, the shoulders are the most commonly injured body part as a result of competitive swimming.

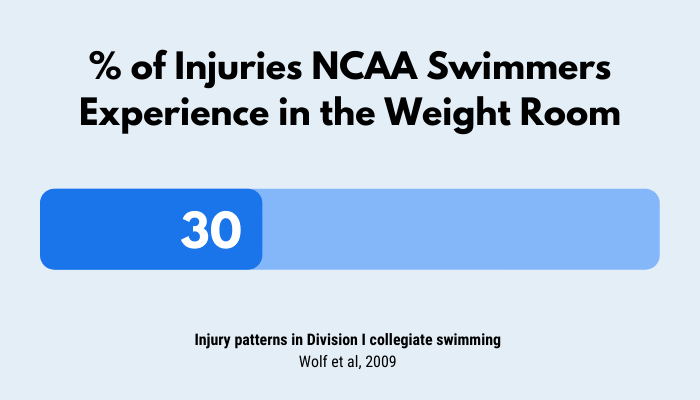

Studies have shown a large number of swimmers will experience injury to their shoulders over the course of their swimming careers:

- One study showed 47% of collegiate swimmers having experienced shoulder pain that lasted 3 weeks or longer (with the same study reporting 48% of masters swimmers experiencing it as well despite half the workouts of the collegiate swimmers).

- A study of over 1,200 American club swimmers found swimmers presently experiencing shoulder pain ranging between 10% in the younger age groups, and 26% of national team swimmers experiencing pain at the time they were surveyed. Using a kick-board and swim paddles were also reported to aggravate shoulder pain.

- Another study done in Australia on 80 of their elite swimmers aged 13-25 found that 91% of them were experiencing shoulder pain. When given an MRI, 69% of the swimmers showed inflammation of the tendon of the supraspinatus muscle. (This bad boy helps to keep your shoulder stable and helps lift the arm sideways—which is why when you have tendonitis in this spot that it hurts when you recover the arm.)

- And lastly, when the University of Iowa’s men’s and women’s swim team was tracked and monitored for a period of five years the shoulder was the most reported injured body part, followed by the neck/back. Freshmen, in particular, tended to suffer injury more often—sometimes twice as frequently—than their teammates.

These studies and stats tell us what most swimmers and those around the sport already intuitively know—that swimmer’s shoulder is frighteningly common.

What are the Causes of Swimmer’s Shoulder?

Swimmer’s shoulder can feel perplexing for the swimmer who feels like they are doing everything right in the water. They will be swimming along, like they have been for weeks and months, and then suddenly, whammy.

What happened? Why now?

Causes include:

Shoulder fatigue

Researchers surveyed 100 college swim teams and 100 masters swim teams and asked swimmers about their history with swimmer’s shoulder. Both groups (47% and 48%) of swimmers had experienced shoulder pain lasting longer than three weeks.

Interestingly, paddle use, perceived range of motion and flexibility, and breathing side didn’t predict shoulder pain.

But more than half of the swimmers from both groups reported that longer training and distance tended to aggravate shoulder pain, indicating that fatigue was the chief cause of shoulder pain for swimmers.

Fatigue is an umbrella term that includes: Not resting properly between reps/workouts, excessive training, and overuse.

Muscular imbalances in the shoulder

Another group of elite competitive swimmers experiencing shoulder pain had a range of motion and internal/external strength compared to non-swimmers of the same age, sex, and dominant side.

Most notably, the internal rotation strength of the swimmers was significantly stronger than the control group.

Swimming with poor technique causes problems in the shoulder.

Swimmers understand the importance of swimming with excellent technique. But swimming with proper form isn’t just to swim more efficiently, it also helps you avoid injury.

Body roll is the big one when it comes to swimmer’s shoulder, with too much or too little body roll causing issues for the shoulder:

- Too much body roll means the hand is going across the mid-line during the hand entry, placing the shoulder at a mechanical disadvantage.

- Too little body roll forces the recovering arm to jam up the shoulder joint.

Optimal body roll means you are stronger and faster while also not needlessly smashing your shoulder.

Poor posture

Swimming is an anterior-dominant activity. The front o fyour body is getting the bulk of the work and attention, and as a result, we become strong on the front of our body, while the lower back, glutes, hamstrings are neglected.

Combine this with the general shoddy posture we develop from sitting and slouching, and we create a perfect combination for injury in the water.

From being slumped over our desks, on the couch, in bed, or during our countless staring matches with our mobile device, the posture we carry for the 22 hours of the day we aren’t in the pool inevitably bleeds into our swimming.

And when we have bad posture in the water we are creating the ideal circumstances for the inevitable shoulder injury.

1. Sleep on your back.

Having sore shoulders is inevitable over the course of our swimming careers.

It’s bad enough that they are tired and sore after a tough workout, but it’s even worse when sleeping improperly on them at night ends up causing even more pain.

I cannot count how many times I woke myself up at night from a streaking pain in my shoulder, flashing all the way down to my elbow because I was splashed across my bed on my front with my bad shoulder wrapped up under my head.

Whether you go full-blown fetal, semi-prone while giving sweet cuddles to a pillow, or in any other variation of side sleeping, the default setting for most of us is on the side.

The problem for swimmers (and their sore shoulders) is what happens when they place their arm above their head, or roll their shoulders forward. Placing your shoulder out of alignment tends to exacerbate the pain, causing you to wake up in the middle of the night with your shoulder on fire.

The answer?

Lay on your back while you sleep to take the pressure off your shoulder, and to put your neck and shoulders in alignment.

To further place your arms and shoulders back into their socket—where they are supposed to be—place your hand across your chest. If your shoulders still aren’t rolling back far enough place a pillow under your elbow in order to elevate the hand a little bit.

You’ll find this position is especially helpful if you are presently experiencing shoulder pain.

(Shout-out to Kelly Starrett at MobilityWOD for this tip.)

2. Improve your t-spine mobility.

As swimmers we know all about the importance of having flexible shoulders, pecs, ankles and hips. It’s drilled into us from day one with the myriad of stretches and arm and leg swings we do from our age group days and up.

But if I told you that something called your thoracic spine played a major role in your swimming, would you have the faintest idea what I was talking about?

The thoracic spine refers to the part of your spine located in the upper and middle back.

This bad boy is built for rotation, it’s built for flexion, and it’s built for extension.

When swimmers have poor t-spine mobility it affects a whole bunch of things, not just how likely you are to spend the last half of the workout doing vertical kick in the dive tank instead of completing the workout with your teammates.

You can’t rotate as well to breathe, causing over-rotation of the hips. Your shoulders and chest roll forward and inwards. And it also restricts your undulation, hindering your dolphin kicking.

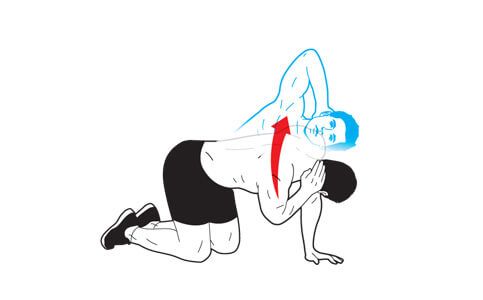

Here is a two-pack of simple exercises to incorporate into your warm-up to boost your t-spine range of motion:

Foam roller thoracic spine extension. 8 deep breaths. You will find yourself extending further back. Suck belly button in. Roll up another vertebrae or two and repeat. Support your head with your hands to avoid undue strain on your neck.

Quadruped t-spine rotation. On all fours put a hand behind your head and dip below your opposing shoulder, leading with your elbow. Keeping your head straight and hips stable—don’t twist your hips, in other words—leading with your elbow, rotate your shoulders so that your elbow ends pointing at the ceiling.

3. Improve scapular stability.

What are your scaps? And why are they important? And more importantly, why is it so fun to say “scaps”?

During my day they were neglected in favor of more rotator cuff work. Over the past decade or so research has begun to show just how critical a role they play, with swimmers with less than awesome scaps generally suffering from added stress to the anterior shoulder capsule, a rise in the likelihood of rotator cuff compression, and decreased neuromuscular performance in the shoulder.

Okay, so those were some sciencey words.

To break it down, the scaps provide a solid base from which your shoulder joint can exert additional force and power.

Stable, strong scaps = more power and speed in the water. (And less likelihood of injury.)

An easy way to develop scap stability is to throw a basic standing row into your warm-routine. You can use an elastic band, cable machine, or my favorite, TRX.

Keep your elbows tight, feel the squeeze in your scaps at the end of each rep, and perform the movement with control.

4. Strengthen your rotator cuffs.

For as long as I can remember I have watched swimmers do internal and external rotators with bands on deck.

I’ve banged out a large number of them myself, and continue to do so to this day as part of my daily warm-up. It’s been so intertwined with the term shoulder injury that it has turned most swimmers and coaches into armchair physiotherapists.

“Aww yeah, shoulder is acting up. Gotta get back on the internal and external rotators.”

A word of caution with doing endless sets of rotator cuff strengthening exercises, however.

Performing work on the rotator cuff isn’t a cure all for shoulder issues. It should be used as a preventative tool, and one that is lower on the totem pole than having overall mobility in your t-spine and stability.

Dr. Erik DeRoche, USA Swimming’s team chiropractor on the 2012 and 2014 World Championship teams as well as the University of Michigan’s team chiropractor at NCAA’s in 2012, backs this up:

“Commonly, I see swimmers performing rotator cuff strengthening exercises as a fix for shoulder pain.

This, while a part of therapy, is one of the last things I do on the continuum of care.

Establishing mechanical deficits is primary…”

Which transitions into probably the most critical preventative measure you can take against shoulder injury…

5. Swim with excellent technique.

Having great posture outside of the water is fantastic, and will serve you well.

But if you forgo any thought of maintaining solid posture in the water, than you are still leaving yourself open to taking on shoulder injuries in the future.

Remember that swimming is a resistance exercise, just like weight lifting or any other kind of resistance training, and that achieving proper technique and form should be your over-riding objective before adding any kind of load (intensity and/or volume) in the water.

On top of the risk that you are putting your shoulders at, swimming with stinky posture means you are losing out on substantial power in the water.

Don’t believe me?

For a moment round your shoulders forward, and try to simulate your stroke. Are you getting a good range of motion? Nope. Are you using your core, back and arms to the best of your capability? Certainly not.

In other words, having excellent technique and mechanics in the water is absolutely critical to both swimming fast and staying clear of nagging shoulder injuries.

Dr. DeRoche:

“Poor swimming mechanics is what I see most commonly creating shoulder ‘issues’ in any swimmer.

The primary factor which contributes to impingement syndromes that I see in my office is a thumb-first hand entry in the crawl/freestyle stroke.

What this hand entry creates is internal rotation of the arm/hand and ‘closes’ off/pinches the soft tissues on the inside (medial) arm and disallows for adequate reach and therefore a less than optimal catch.”

Russell Mark, high-performance consultant to USA Swimming, agrees (emphasis mine):

“Repetition alone isn’t enough to injure your shoulder. Repetition of bad technique is. It’s so easy – and incorrect – to swing your arm behind your body when you swim.

- In freestyle, a wide hand recovery is more natural and easier on your shoulder than a recovery with your hand close to your body. Swing your hand and arm around to the side.

- During the pull phase, make sure your hand doesn’t scull wide at the same time your body is rotated.

Brent Hayden, Olympic bronze medalist in the 100m freestyle in 2012, and winner of the 100m freestyle at the 2007 FINA World Championships had this to add for all you freestylers out there:

“…eliminate zipper drill and over-emphasis of high elbow freestyle, which often involves shrugging (therefore impinging the shoulder) the arm through the recovery. Instead aim to come around naturally like an arm swing with a soft elbow.”

6. Make pre-hab routine.

Swimming is a big investment of time.

I get it—between all of the two-a-days, 4-day meets, and more meters and yards than you could possibly count—the sport demands much from us.

In addition to school, work, and what passes for a social life it is hard to put together the extra time to insure the health and well-being of our shoulders.

But you can avoid having to put out the fires of chronic or sudden shoulder injuries by spending just a handful of minutes per day before your workout priming your body and shoulders for not only high-performance swimming, but a movement that is less likely to result in injury.

This means making your pre-hab work habitual.

Routine.

Simply a part of your training. As essential as your goggles and suit.

Travis Dodds of Vancouver based InSync Physiotherapy notes that most shoulder injuries are avoidable:

“My view is that this injury is almost entirely preventable.

If an athlete is starting to feel stiffness or mild shoulder pain they should focus more on prehab.

If it lasts more than a few days or becomes severe enough to limit their stroke or range of motion they should seek treatment, even if the pain doesn’t seem that bad. Swimming through pain simply limits your technique.”

Make your pre-hab a part of your daily warm-up routine, something that you don’t even have to think about—just something you do—and you will be well on your way to swimming injury-free this season.

7. Stay positive and do what you can with what you have.

Being injured is super frustrating—I totally get it. But on the bright side, there are things you can do to get better while you are on the mend. Natalie Coughlin, Michael Phelps, Caeleb Dressel—these are just some of the swimmers who trained around their injuries and emerged faster as a result.

There are lots of options for training around, up, and under your injury, but here are a couple of my favorites:

- Swim with fins. Adding fins to your swimming increases the propulsion coming from your legs and reducing the demands and stress on the shoulders. Warming up with fins is an especially smart move as it will ease your shoulders into the work.

- Vertical kicking. I am a huge fan of vertical kicking. You need little space in the water to do it, can use fins/DragSox/weight belt to increase difficulty, develop the up and down phases of the kick more evenly, and don’t risk aggravating your shoulder using a kickboard.

In Summary

Start with solid mechanics in the water. Have killer posture in and out of the pool. Seek the advice of your coach and a qualified therapist to deal with your specific condition.

And go forth with less pain in your shoulders my chlorinated homies.