How to Improve Your Pacing Skills

Looking to up your pacing skills in the pool? Here are some actionable pacing tips and tools to help you master pace and your performance on race day.

Sydney, Australia – September 20, 2000

For the country of Australia, the Sydney Olympics in the pool were a crushing success.

Ian Thorpe dominated the pool in the mid distance events. Grant Hackett took the mantle from distance legend Kieren Perkins to crush the mile, the Aussies going 1-2. The men won the 4x100m freestyle relay to dethrone the Americans in an event they had never lost in the Olympic programme.

While the Aussies weren’t as strong on the women’s side, they did have one swimmer who had attained legendary status in the swimming-crazed nation.

Susie O’Neill, or “Madame Butterfly” as she was known.

O’Neill had completely owned her best event, the 200m butterfly stroke for the previous six years, including a gold medal at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Several months earlier, in the same Sydney pool, she had broken American Mary T. Meagher’s long standing world record (nearly 20 years).

SEE ALSO: How to Develop an Awesome Underwater Dolphin Kick (Guide)

On top of being the undisputed champ in the 200 fly, earlier that week in Sydney she had also won the 200m freestyle, further catapulting the home nation’s hopes of butterfly gold.

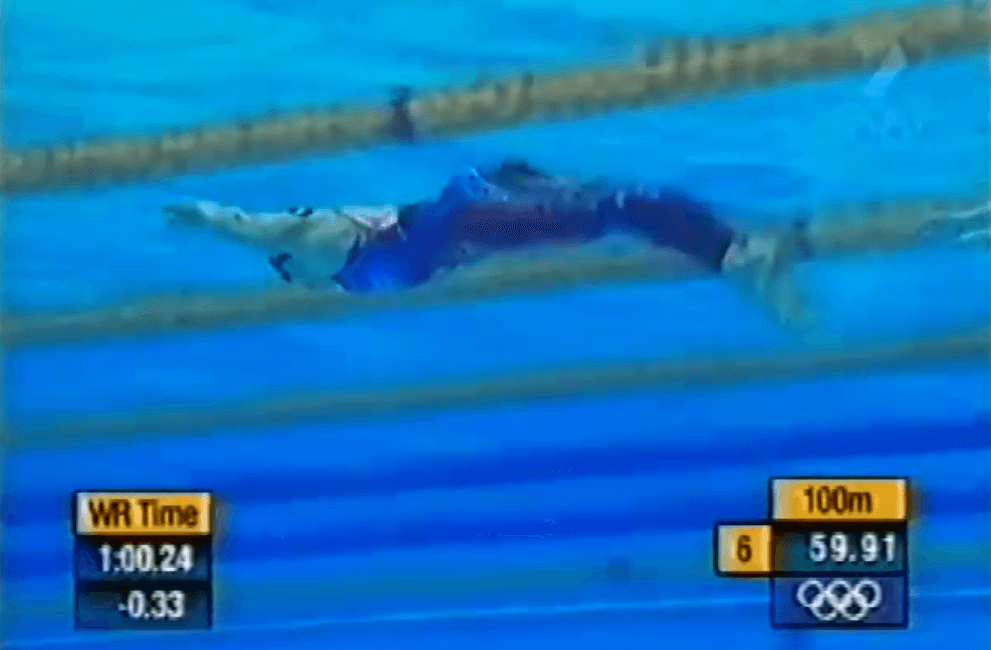

In the final that night O’Neill qualified first, with countrywoman Petria Thomas above her lane 5. With all eyes on the Aussies—the thundering ovation O’Neill received when introduced left no doubt to who the sell out crowd was backing—it was easy to overlook the smiling American in lane 6.

To understand just how radical Hyman’s kick was is to understand how underwater kicking was regarded at that time.

Even then, in the year 2000, the underwater dolphin kick was viewed as an aberration, the black sheep, a skill that was poorly understood and rarely implemented in training.

SEE ALSO: Michael Phelps’ Underwater Dolphin Kick Training (Video)

While most swimmers nowadays accept that the UDK is part-and-parcel with every event from the 50m splash-and-dash to the distance events, back then it wasn’t. Even in the butterfly events.

Hyman had been a practitioner of the extended underwater dolphin kicking since 1993, emulating some of the other top butterfliers in the world, including Mel Stewart and Denis Pankratov.

Inspired by an article in Scientific American that showed fish could used spinning eddies to increase the velocity they attained under the water, Hyman’s coach Bob Gillette at the Arizona Desert Fox Swim Team applied this to Hyman’s dolphin kick and had her turn on her side.

It didn’t come without difficulty, however, taking her about a year to get used to kicking on her side, especially trying to maintain a straight line as there was no black line to stare at as a point of reference.

To build up the powerful legs required to maintain the power and velocity—particularly for the grueling 200m long course distance—Hyman worked relentlessly doing underwater work with and without a monofin.

In defending the emphasis on the underwater kick, Hyman explained herself well:

I’m not six feet tall, and for me to compete, I have to do it the best way for me. Skill and innovation were what got me to this level. My coach and I developed this and we’re not breaking any rules. In fact, lots of people are doing the underwater. I think it would be a shame if they changed the rule (to limit the distance of the underwater kick) but if they did I would just have to change my training.

In the winter of 1996 Hyman put her powerhouse legs to work, dropping nearly half a second off of the world record in the 100m butterfly (SCM) in Sainte-Foy, Quebec, using her trademark kick.

Despite this performance, there weren’t many who were expecting Hyman to dethrone the reigning Queen of the butterfly that September in Australia.

Especially not in Sydney.

Especially not in a long course pool, where the effect of Hyman’s superior underwaters would be halved compared to the short course pool.

And especially not in the taxing distance of the 200m butterfly.

When the finalists left the block that night Hyman was the slowest to react.

Despite this, she kicked out to nearly 15m and popped up in a slight lead with Thomas in 5.

Off the 50m wall Hyman gained a half body length lead on Thomas, and nearly a body length on O’Neill.

Even though Hyman didn’t kick out the full 15m on subsequent walls, including the third turn, where she pumped out 7-8 kicks—which was good enough to push her out to around 12m—it still contrasted sharply against O’Neill who surfaced at 5m and breathed off her first stroke.

SEE ALSO: 5 Reasons to Work On Your Underwater Dolphin Kick

It was clear to see that any dent that O’Neill tried to make in between walls was quickly negated by Hyman’s powerful breakouts.

With O’Neill charging hard on the last 50m, Hyman didn’t relent, surfing into the wall in a time of 2:05.88, just 7/100’s off of O’Neill’s world record mark, but good enough to shave over a second off the former world record holder’s (Meagher) mark of 2:06.90.

For Hyman, who had battled the naysaying that comes with being viewed as a one-trick pony, and who had overcome the implementation of the 15m limit to how far swimmers could perform the kick underwater, the victory was nothing short of overwhelming.

The surprise, shock and joy that envelops her face as she realizes that she has won is a welcome surprise when most athletes would prefer to thump their chest or react with stoic blandness.

As she would recount after the race,

I’ve played it over so many times in my head, but I never thought it would come true.

Here is the race video from Sydney:

Want to take your dolphin kick to the next level?

I put together a comprehensive 3,000+ word guide on improving your underwater dolphin kick. From flexibility, to strength training, to technique (and even some bonus sets), you will learn everything you need to know about how to dolphin kick like a boss.

Click on the image below and enter your email address to get instant access to the guide, sets, and a faster underwater dolphin kick!

Olivier Poirier-Leroy Olivier Poirier-Leroy is the founder of YourSwimLog.com. He is an author, former national level swimmer, two-time Olympic Trials qualifier, and swim coach.

✅ Free shipping on Orders over $49

✅ Price Match Guarantee

✅ Best selection of gear for training and competition

✅ Fast and Easy Returns

“This is the best book I have ever seen concerning mental training.” — Ray Benecki, Head Coach, The FISH Swim Team

Looking to up your pacing skills in the pool? Here are some actionable pacing tips and tools to help you master pace and your performance on race day.

Looking for tips on how to use a drag chute for improved swim performances? Read on for some proven tips, sets, and pointers for training with a chute.

Ready to take your swimming to the next level? Here are seven ways that a drag chute can help you become a better and faster swimmer.

Wondering if a swim bench can help improve your swimming? Here are six benefits of swim benches for better technique, more power, and faster swimming.

Not breathing into the walls is one of the fundamental skills developing swimmers are taught. Here is how powerful a no-breath approach is for turn and swim speed. Strong training habits are something swimmers hear a lot about from their earliest days of their competitive swimming careers. The greatest hits

Drills with a swim snorkel are one of the best ways to maximize engagement and skill development. Here are five swim snorkel drills to try for faster swimming.

SITE

SHOP

GUIDES

LANE 6 PUBLISHING LLC © 2012-2025

Join 33,000+ swimmers and swim coaches learning what it takes to swim faster.

Technique tips, training research, mental training skills, and lessons and advice from the best swimmers and coaches on the planet.

No Spam, Ever. Unsubscribe anytime.