10 Motivational Swimming Quotes to Get You Fired Up

Looking for some awesome swim quotes? Give this list of motivational swimming quotes a look the next time you need to rock and roll in the pool.

The American men have a long history of dominating the backstroke events at the Olympics. From John Naber in 1976, to the dominance that men like Jeff Rouse, and more recently, Aaron Peirsol, the consistency that the US has placed men on the podium is without peer.

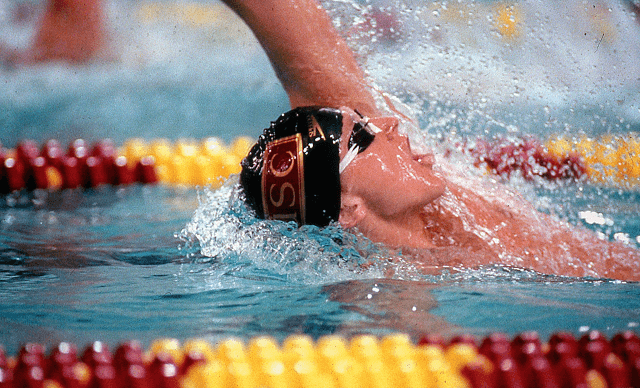

One such athlete who not only dominated both backstroke distances, but also did so in the face of overwhelming difficulty, was Lenny Krayzelbrug.

Born in the Ukraine, Krayzelburg and his parents left the Soviet Union in 1989 and headed for Los Angeles. Battling the difficulties of the language barrier and extensive commutes to get to practice and back, Krayzelburg perservered, eventually ending up the University of Southern California (Naber’s alma matter as well), training under legendary coach Mark Schubert.

In 1998 he became the first swimmer since 1986 to win both the 100m and 200m backstroke titles at the FINA World Championships in Perth, Australia. Two years later, at the Sydney Olympic Games, Krayzelburg would again prove dominant, breaking the world record in the 100m backstroke in a time of 53.72, besting the Olympic record in the 200m backstroke by powering to gold in 1:56.76, while also leading off the world record-beating American men in the 4x100m medley relay.

In the months following Syndey, with Krayzelburg set to make a run for Athens in 2004, he injured himself while running sprints on a treadmill.

Twisting his ankle, he landed awkwardly and ended up tearing the ACL in his shoulder, eventually undergoing surgery twice in the span of a year, with the second one taking place in September of 2001, where he underwent full reconstructive surgery on his ACL.

When swimmers (or anyone for that matter) get injured, most will rush to get back to the pool. Swimmers understand better than most that time is limited, it is precious, and that every second out of the pool is an opportunity wasted, sand sipping through the hourglass.

For Krayzelburg it was no different:

When I look back on all my injuries and rehabs that I went through, I wish I could have approached them differently. I was always trying to get back in shape too fast and not being fully considerate of the healing process post surgery. As long as I felt good I was pushing myself to the limit as I always did when I was healthy. As I reflect back on it now, I realize that I needed to be more careful and thorough in my rehab process, give time for the injury to heal properly especially after surgery, and build the strength back slowly.

Despite the reconstructive surgery, by the fall of 2003 Krayzelburg continued to feel pains and aches in his shoulders, with not only the tendon in his shoulder still torn, but the shoulder capsule itself was loose, which was not helping the healing process, and if anything, probably even causing further damage.

With Olympic Trials not even 8 months away, the decision was made to train through it. In order to do so, he had to alter his approach in the water:

The decision was pretty simple, train with the injured shoulder for the next 8 months and give it my best shot at Olympic Trials. To preserve the shoulder and avoid doing more damage to it, I had to adjust my training. For the next three months I did not use my left arm while training. I did mostly kicking and swimming with one arm. I also spent a lot of time on the stationary bike trying to keep my endurance up, because of my limited ability in the water.

Perhaps most notably, Krayzelburg never lost sight of the goal, and remained focused and optimistic. I cannot count how many times I have seen athletes fall to the wayside when injuries force them to adjust or alter their preperation.

Being flexible with your training, and finding the positive out of a bad situation is key, and Krayzelburg was committed to doing both:

Although my situation was pretty bleak, together with my coach we found ways to still get the most out of our training sessions and look to improve in other aspects of my preparation. Limited to kicking only, I set a goal for myself in training sessions to keep up with my teammates while they were swimming.

Of course I could only do it for so long, but I knew giving myself this challenge I would become a better kicker, and make something positive out of a bleak situation.

At the Olympic Trials Krayzelburg passed on the 200, instead choosing to focus all of his efforts and preparation for the 100m backstroke. He would place 2nd behind Aaron Peirsol, who he was training with under Dave Salo at the time, and punched his ticket for Athens.

At the 2004 Olympics he would come 0.02 short of a silver, 0.01 short of a bronze in the 100m backstroke final, unable to repeat at Olympic champion.

He would, however, add gold as a result of his participation on the US men’s 4x100m medley relay, giving him 4 Olympic gold medals over the course of his career.

After retiring from the sport, Krayzelburg, set his sights on helping spread swimming to the masses, particularly with underserved communities across the United States.

First known as the LK Swim Academy, Krayzelburg’s transition from athlete to mentor is evident in his work at his academy, where he focuses on water safety and provides swim lessons to children and adults.

3 Backstroke Sets with Olympic Champion Lenny Krayzelburg. Lenny Krayzelburg won the 100 and 200m backstrokes at the Sydney Olympics and broke all the long course backstroke world records in the book. Here are three backstroke sets that Krayzelburg did on his way to becoming a backstroke legend.

Olivier Poirier-Leroy Olivier Poirier-Leroy is the founder of YourSwimLog.com. He is an author, former national level swimmer, two-time Olympic Trials qualifier, and swim coach.

✅ Free shipping on Orders over $49

✅ Price Match Guarantee

✅ Best selection of gear for training and competition

✅ Fast and Easy Returns

“This is the best book I have ever seen concerning mental training.” — Ray Benecki, Head Coach, The FISH Swim Team

Looking for some awesome swim quotes? Give this list of motivational swimming quotes a look the next time you need to rock and roll in the pool.

Missy Franklin’s book Relentless Spirit details the triumphs and tribulations on the path to becoming an Olympic champion. Here is a review of the book, along with key takeaways, quotes and highlights…

American swim star Missy Franklin captivated the world during her reign as one of the best swimmers on the planet. Here’s how she built her self-confidence going into big swim meets.

If you want to swim faster and maximize your preparation in the water, make sure you are focused on real solutions and not fake problems.

Ever wondered why some swimmers always swim ridiculously fast on relays? Here’s how the kind of motivation you use behind the blocks influences how you perform in the water.

This is the ultimate guide for helping age group swimmers get highly motivated. You are going to learn about some proven techniques and tools that you can start using today to light your motivation on fire. (And keep it burning bright after that first burst of motivation fades away.) If

SITE

SHOP

GUIDES

LANE 6 PUBLISHING LLC © 2012-2025

Join 33,000+ swimmers and swim coaches learning what it takes to swim faster.

Technique tips, training research, mental training skills, and lessons and advice from the best swimmers and coaches on the planet.

No Spam, Ever. Unsubscribe anytime.